The

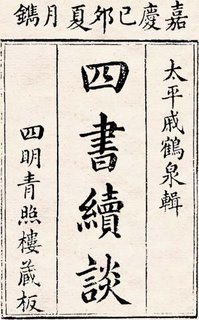

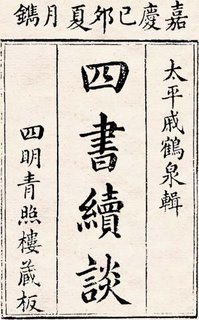

Sìkù Quánshū (

四庫全書), that is,

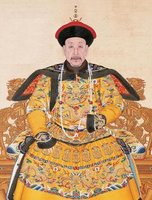

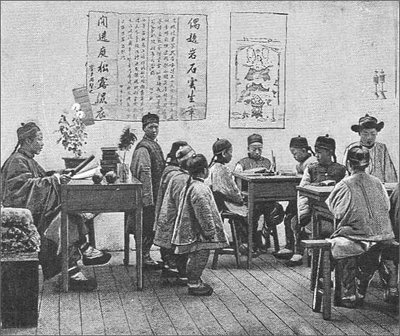

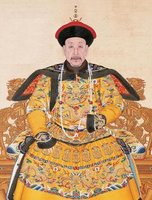

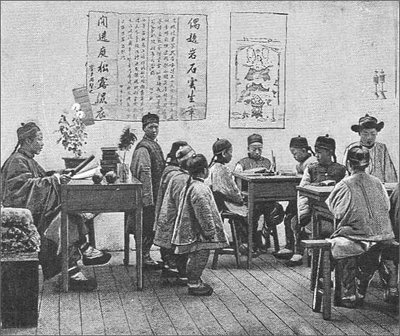

All the Books from the Four Treasure Houses, was the most monumental editorial undertaking ever conceived in the history of mankind. Initiated in 1773 by Emperor Qianlong (1736-1799) – remember, the one who replied to the King of England in 1793 that “We possess all things, and we have no use for your country’s product; it is your duty to understand my intentions and reverently to obey my instructions” –, and carried out in nine years under the direction of the 300 most reputable scholars of the Empire, headed by Ji Yun 紀昀 (d. 1805) and Lu Xixiong 陸錫熊 (d. 1792), it included every work ever written in the course of the five thousand years of Chinese history and judged worth to be admitted, by this very act of canonization, to the hall of immortality. The Four Treasure Houses meant the four conventional branches or classes of literature – 經

Jing, the Classics, 史

Shi, the Histories, 子

Zi, the Masters, and 集

Ji, the Collections –, thus this most comprehensive encyclopedia ever compiled covered

every field of knowledge, from literature through philosophy and its classical authors, history, genealogy, biography, geography, politics, governmental rules and regulations, strategy, economics, society, astronomy, science and technology to medicine and more,

all complete with the authoritative commentaries and explanations. The books incorporated from the Four Houses in the

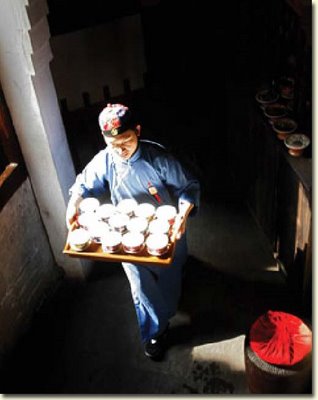

Quanshu were 36.000 by volume, 2.3 million by page and 800 million by Chinese character. Trabajo de chinos, insomma.

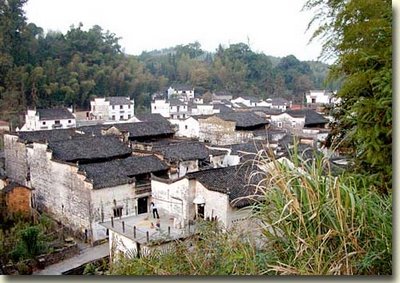

The nine years of its compilation were followed by eight more years of the preparation of six more copies by the work of almost 4000 scribes. Then the seven copies were solemnly deposited in seven special libraries throughout the country, established for the purpose with imperial decree. And this carefulness has proved really foresightful. The thereafter following two centuries of Chinese history abunded in catastrophies, upheavals, foreign and civil wars and destructions, so that only three of these copies – the Wenjinge in Hebei, the Wensunge in Shenyang, and the princeps, the Wenyuange of the Forbidden City – have been intactly preserved. It was this latter, the Wenyuange, that was first photocopied in the 1930s by the Commercial Press, then published in 1500 volumes – already in Taiwan – by the same Commercial Press in 1983-86. This rare edition was further published in Shanghai in 1987, and now scanned page by page and made available in electronic form here. Trabajo de chinos.

Recently the complete collection has been published as a full-text digital database by Digital Heritage in Hong Kong (2004) as well, but this edition, although not horribly expensive – the China Publishing House offers it for 980 USD – only can be found in a handful of libraries throughout the world. If you are responsible for acquisitions in your library, or are on good terms with one such person, do consider ordering it. And in the same thought, er, uhm... don't forget about the Studiolum CDs either.

The annotated catalogue of the Siku Quanshu, compiled by Ji Yun in 1798, and known as Siku quanshu zongmu tiyao 四庫全書總目提要 [General catalogue of the Siku quanshu, with descriptive notes] was published in Beijing as a reprint in 1965, and in a revised and enlarged edition in 1997.

A concise overview of the works included in the Siku Quanshu can be found here (in Chinese only).

The only monography on this collection available in a Western language seems to be the one by Guy, R. Kent, The Emperor's Four Treasuries: Scholars and the State in the Late Ch'ien-lung Era. Harvard: Harvard University Press, 1987.

Desde hace algo más de un año, José Manuel Lucía Megías se ocupa en recopilar ediciones ilustradas del Quijote y de organizar las imágenes en un gran archivo. Hoy nos ha dicho que ya pueden encontrarse hasta 7.284, extraídas de 160 ediciones diferentes localizadas en bibliotecas de todo el mundo. Verdaderamente, no está nada mal.

Desde hace algo más de un año, José Manuel Lucía Megías se ocupa en recopilar ediciones ilustradas del Quijote y de organizar las imágenes en un gran archivo. Hoy nos ha dicho que ya pueden encontrarse hasta 7.284, extraídas de 160 ediciones diferentes localizadas en bibliotecas de todo el mundo. Verdaderamente, no está nada mal. de los siglos XVIII y XIX entre las que alberga esta colección. Nos promete José Manuel que pronto estarán incorporadas.

de los siglos XVIII y XIX entre las que alberga esta colección. Nos promete José Manuel que pronto estarán incorporadas.